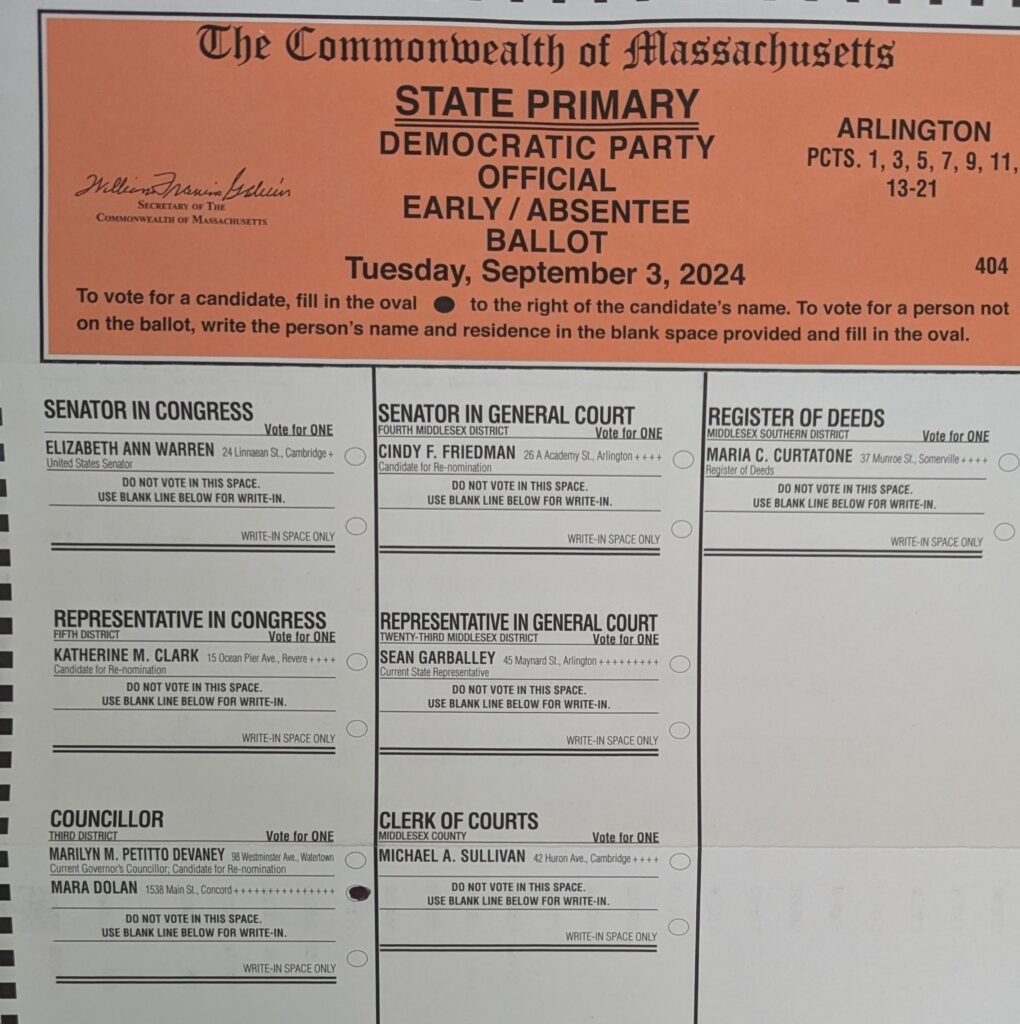

It was pretty quick to fill in my Massachusetts ballot this year:

Yup, only one contest out of seven had more than one choice. Technically this is not the real election, it is the election for nomination as the Democratic Party’s candidate, but for every office listed except U.S. Senator, it is the real election because there are no Republican Party nominees. (And for U.S. Senator, incumbent Senator Warren will win easily despite having a nominal opponent.)

So what about that one contested election, Councillor, Third District? Most voters have no idea what this position is. The Governor’s Council has the power to approve appointments, pardons, and commutations. The incumbent, Marilyn Petitto Devaney, has held the seat for 25 years. Devaney’s electoral history is a perfect example of what is wrong with American elections.

In 1998, Cynthia Stone Creem declined to run again after serving two terms as the Councillor for the Third District. Eight candidates jumped in to run for the “open” seat. Devaney finished first in the Democratic primary with 18.1% of the vote, just 360 votes more than the next-place finisher. Only 95,000 people participated in the Democratic primary in that district that year, and more than 25,000 of them skipped the Councillor’s race–more than twice the number that voted for the winner and many times more than the 360 who decided the outcome. The 69,000 voters who voted in the election were a small fraction of the 257,000 who voted in the general election two months later. (Two years later, 356,000 voters showed up for the general election in that district, when the U.S. presidency was on the ballot.)

Despite being rejected by 88% of the voters in a low-turnout Democratic Primary, Devaney cruised to an easy victory in the General Election for a seat that has been held by the Democrats since at least 1970. Devaney readily beat a single challenger in an extremely low turnout Democratic Primary in 2000. For the next three elections, 2002, 2004, and 2006, Devaney had no opponent in the primary (see Table below). Between 2008 and 2018, she faced one or two opponents each year. In two of those years, she raised more than twice as much campaign funds as her nearest challengers. But in most years, the challengers had more money, including twice as much in 2012 and 2014. She handily beat them all by margins ranging from 7 to 20 percentage points. In 2018, she was outspent $38,000 to $240,000. Even that enormous cash haul–for an office that still pays only $36,000 annually–was not enough: she won by 12 percentage points. The next year, no one even tried to run against her.

| Election Year | Devaney Receipts | % Devaney Receipts Loan from the Candidate | Main Opponent Receipts Total | Devaney winning margin |

| 1998 | not available | not available | not available | 0.5% |

| 2000 | not available | not available | not available | 14.5% |

| 2002 | $200 | 0% | n/a | unopposed |

| 2004 | $1,530 | 0% | n/a | unopposed |

| 2006 | $1,995 | 0% | n/a | unopposed |

| 2007 | $1,260 | 0% | n/a | unopposed |

| 2008 | $7,810 | 0% | $33,005 | 19.9% |

| 2010 | $26,872 | 0% | $11,560 | 13.5% |

| 2012 | $28,088 | 0% | $51,378 | 7.20% |

| 2014 | $28,740 | 0% | $53,073 | 8.80% |

| 2016 | $32,069 | 82% | $12,720 | 19.1% |

| 2018 | $37,375 | 94% | $240,453 | 12.4% |

| 2020 | $695 | 0% | n/a | unopposed |

| 2022 | $22,800 | 94% | $56,219 | 1.7% |

| 2024 | $9,900 | 92% | $130,306 | -4.4% |

| TOTAL | $199,335 | $588,715 |

Devaney’s power of incumbency finally began to wane in 2022. In that year, public defender Mora Dolan raised $56,000 in her effort to unseat Devaney, who did not solicit individual campaign contributions, but instead almost all of the $23,000 available to her campaign came from her own personal loan. (The two prior times she had challengers, almost all of her resources also came from loans from her own money.) Nevertheless, Devaney held on, but by the closest margin of her career: only 1,658 votes or 1.7%.

In 2024, Dolan was a shark smelling blood. She received endorsements from one U.S. Senator, four U.S. Representatives, four of the members of the Governors Council (that is, more than half of those representing districts other than the Third), the State Auditor, five State Senators and twelve State Representatives. Dolan raised $130,000. Devaney barely tried: she spent only $10,000, almost all from a loan to herself. Despite the lopsided spending and endorsements, Dolan won, but by only 4.4 percentage points. At 85 years of age and after 25 years in office, and having come to close to losing the prior election, the incumbent was still hard to beat.

Why is that? I don’t think it’s because voters loved her work. Incumbents have built-in advantages. For many offices they have a fund-raising edge, since they are happy to collect campaign funds from businesses and lobbyists who have a stake in their votes. But not so with the sleepy Governor’s Council.

It’s simply that when voters know nothing about the candidates, they tend to vote for the incumbent. In normal elections, party names can give voters important signals about who to vote for. In party primary elections, all candidates share the same party label. Massachusetts lets candidates in primary elections use eight words to describe the current or former public offices they hold or have held, and incumbents may also include the words “candidate for renomination” (MGL Ch. 53 Sec 45). This law was adopted before 1921, and the only change subsequently was to give veterans the option of including the word “veteran.” Other candidates, no matter how illustrious their resumes, may not provide any information about their experience (nor their political views).

Not only members of the Governor’s Council but also members of the State Legislature benefit from this affirmative action for incumbents. Remember Cynthia Stone Creem? The reason she declined to run again for the Third District of the Governor’s Council in 1998 was that a Senate seat had become “available” because its occupant, Lois Pines, decided to run for Lieutenant Governor. Creem had one opponent in the Democratic Primary for the 1st Middlesex and Norfolk District that year, and she beat him in a two-to-one margin. She then faced no opponent in the general election. And in every year since, she has run unopposed in the general election, with the sole exception of 2004 when she beat a Republican opponent 77% to 28%. After the first win in 1998, she was unopposed in the Democratic Primary every year since then with the sole exception of 2010. In that year, Charles S. Rudnick deigned to run against Creem. He raised $230,000 of which $105,000 came from his own pocket. Creem spent $166,000, about half from newly raised sources and half from her war chest of prior fundraising. Fewer than 18,000 people voted in the primary in a district that sees more than 80,000 voters in a presidential year. (The candidates together spent $22 per vote cast!) Creem won, 72% to 28%. Rudnick learned an expensive lesson: do not challenge an incumbent. That lesson was well heeded: no one has challenged her since. Currently Senator Creem at age 81 is Majority Leader of the Massachusetts Senate.

The electoral history of Deveney and Creem is not at all unusual, as I wrote in Democracy Isn’t Working in Massachusetts. And in the nation at large, more than half of public elections where party names are allowed have only one name on the ballot, as the New York Times found in a recent investigation, A Democracy With Everything but a Choice.

If we are going to have meaningful elections for public office, then we need competition, which means more than one candidate on the ballot. We could greatly increase both competition and participation by eliminating party primaries, by making it easier for candidates to qualify for the ballot, by giving political parties the exclusive right to determine which candidates can use the party name, and by using ranked-choice voting so that, say, 18% of first choices does not guarantee victory. Better yet, we could have multi-winner ranked choice voting so that we could represent diverse viewpoints in our legislatures and councils in proportion to the votes cast. I will say more about why we need these in future posts.

Short of fundamental reform, it would seem that one easy fix would be to remove the ability of incumbents to identify themselves on the ballot, or at least to offer challengers the same eight words to give relevant information to voters. But doing so would likely hurt the re-election chances of incumbents, and every single member of the legislature whose vote would be need to make this change is, of course, an incumbent. So good luck with that.