The 2017 French presidential election has some resemblance to the U.S. 2016 Presidential contest:

The 2017 French presidential election has some resemblance to the U.S. 2016 Presidential contest:

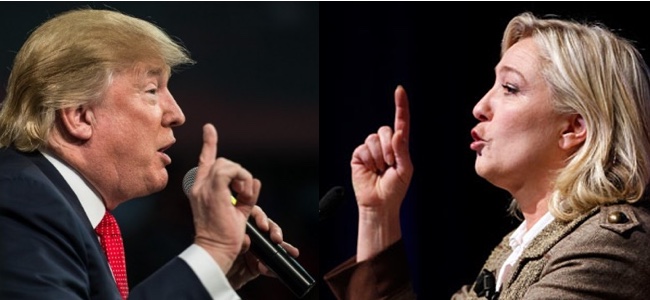

- An anti-immigrant, nationalist espousing populist rhetoric surging in the polls (Marine LePen in the role of Donald Trump);

- A leftist populist far out of the mainstream with a huge following among young people (Jean-Luc Mélenchon playing Bernie Sanders);

- Complete disruption of the two major political forces.

However, the ending will be different. The young upstart centrist, Emmanuel Macron, who finished first on April 23rd, is likely to crush Marine LePen in the second round on May 7. According to all the polls, at least 60% of French voters are likely to vote against LePen. A similar percentage of American voters had an unfavorable view of Trump throughout the 17 months prior to the election. So how is it that Trump was elected, given that most Americans didn’t (and don’t) want him?

As I discussed in a previous post, the key deficiencies in the U.S. case were:

- the so-called “electoral college.” a historical accident that has twice in this millennium led to the defeat of the U.S. presidential candidate with the most votes.

- a turnout of only 59% of eligible voters, depressed in part by recently enacted voter ID laws as well as the long-standing U.S. policy of requiring voters to register in advance (although a few U.S. states have recently adopted automatic registration policies similar to what is used in most other democracies).

- the haphazard non-system of presidential primary elections and caucuses, with participation by less than 30% of voters, most of whom do not have a choice among all the candidates (because many drop out early in the months-long process).

- the Republican Party rules that gave Trump 62% of the delegates with only 45% of the vote;

- the longstanding Republican campaign to demonize Hillary Clinton, abetted by the media’s, and apparently the FBI’s, need to appear balanced.

- the impossibility of including other serious candidates in the U.S. Presidential election other than those of the Democratic or Republican parties.

By contrast, in France:

- The majority rules. If no candidate receives 50%, as is typically the case, the top two finishers contest a second, decisive round two weeks later. Already the French parties are unifying against Marine LePen, as they did against her father Jean-Marie LePen, who lost 18% to 82% in the second round of the 2002 election.

- Most people vote. The 2017 first round turnout was 78%, just a bit below the average for recent years. In most years the turnout holds steady or increases for the second round.

- All candidates participate in one election campaign. Unlike the U.S. primary system, the two-round system allows voters to express their true first choice among numerous candidates (11 in 2017), while knowing they will have a second chance to vote should their least favored candidate be chosen.

The U.S. artificially forces all serious competition to the nominees of the two official parties. By contrast, in France the candidate of the incumbent President’s party finished a distant fifth, whereas the top finisher, Macron, had left the Socialist Party to form his own political movement. The fourth-place finisher, Melanchon, was also the candidate of a new party. Although Sanders was an insurgent outsider who tried to capture the Democratic Party, and Trump was an insurgent outsider who did capture the Republican Party, it is almost inconceivable in America, for many reasons, that a candidate of a new party could be considered a serious contender for President, much less finish in first place. Once Trump captured the Republican nomination, there was no way for anti-Trump Republicans to mount a credible challenge to him in the general election, and thus anti-Clinton voters had no realistic choice other than to vote for Trump.

In short, a combination of anti-democratic features conspired in the U.S. case to make Trump President against the wishes of the majority, whereas in France majority rule and broad participation mean that LePen (the French Trump) will almost certainly not become president.

The French could improve on their system by using ranked choice voting in a single round, which would eliminate the cost (both to the government and to individuals) of holding a second election, and could also make the outcome more closely reflect the wishes of the voters, especially when first preferences show a very small gap between the second and third place finishers (which occurred in both 2002 and 2017), or when there are multiple candidates of similar political orientation with significant followings. In low-profile races, ranked choice voting would probably have a positive effect on overall turnout, but in the French Presidential elections, changing to this system might not have much of an effect on turnout given that it is already generally high in both rounds.