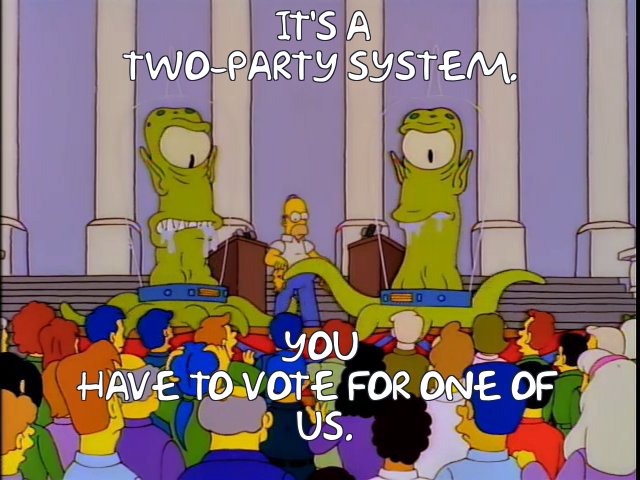

We hear often that America has a “two-party system,” but most people don’t understand that state and Federal laws favoring (what I will call) the two official parties are without precedent among peer democracies; that the system was not designed but evolved over time, and that the web of discriminatory laws violate international democratic norms. As we shall see, the legal status of political parties is one of the central defects of the American political system.

We hear often that America has a “two-party system,” but most people don’t understand that state and Federal laws favoring (what I will call) the two official parties are without precedent among peer democracies; that the system was not designed but evolved over time, and that the web of discriminatory laws violate international democratic norms. As we shall see, the legal status of political parties is one of the central defects of the American political system.

The U.S. Constitution did not create the two-party system–that document doesn’t mention political parties at all. Nor does it specify the electoral system for Congress, only giving the number of Representatives and Senators per state. Today most U.S. Representatives are elected by plurality election in single member districts, but there have been numerous times when multiple Representatives have been elected from a single state-wide district (“at large,” or “general ticket”). Congress has periodically required states to create single-member districts, most recently in 1967. In 46 of 50 states, the winner needs only a plurality (the most votes) rather than a majority; I will return to the other four below.

It is frequently said that the U.S. two-party system is the natural result of plurality elections in single member districts. Maurice Duverger’s famous principle states that such systems tend toward two dominant parties, in contrast to electoral rules using the two-round system or proportional representation. Although there are countries with two dominant parties, no other country in the world has a two-party system like that found in the United States, where the same two parties have dominated politics for 150 years, and have erected strong barriers to the entry of newcomers–while at the same time the possibility for mass party politics as it is known in many countries is not possible here.

The American two-party system of 1840-1900 was very different from the system that emerged later: new parties appeared frequently and had much more electoral success than any today, culminating in the People’s Party of the 1890s, which became the second party in several states and elected, or helped to elect, 45 members of Congress and 11 governors. Voter turnout, among those eligible, was notably higher than today: 70-80% of eligible voters participated in presidential elections. State legislatures created many new regulations of parties and elections between 1890 and 1915 that transformed the American electoral system: the government-printed ballot, prohibition of candidates appearing on the ballot under the name of multiple parties (fusion prohibitions), and direct primary elections. A second series of “reforms” during this period greatly shrank the electorate through the use of voter registration requirements, literacy tests, poll taxes, and white primaries, Although the discriminatory intent of these rules was most evident in their use by Southern Democrats, who managed to remove most blacks and many whites from the electorate, despite the 14th and 15th Amendments, they were also directed at reducing turnout among immigrants and workers in the north.

Over time states further reduced the possibility of competition from new and small parties by making it harder to get on the ballot and by prohibiting losing primary election candidates from running in the general election (“sore loser laws“). Although many barriers to voting were reversed by Congress and the Supreme Court following the Civil Rights Revolution of the 1960s, the barriers to new party participation that are written into state election codes remain almost as strong as ever, and generally have been accepted by the Supreme Court (a topic which I will explore later).

Americans often conflate multiparty systems with parliamentary systems–where the legislature selects the executive (prime minister). However, most former British colonies inherited plurality elections in single member districts, as in the US, but use a parliamentary, not presidential, system of selecting the executive (Canada, UK, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Malaysia and the Caribbean). Even if they have two dominant parties or coalitions, almost all of these countries have numerous small parties that achieve at least some representation, and may even displace one of the two largest parties from time to time.

Most of the countries of South and Central America have presidential systems: when they became independent republics, one of the few models was the United States. However, almost all of them have legislatures elected by proportional representation (e.g., Mexico, Costa Rica, Brazil, Colombia). There are also 17 countries other than the USA that have an elected president instead of a prime minister and a legislature elected by plurality vote in SMDs–except for Azerbaijan, Mongolia, and Yemen, all of these countries are in sub-Saharan Africa. But unlike the U.S., most have more than two parties represented in the national legislature.

Among the 50 most populous countries in the world only Nigeria and the U.S. have no more than two parties represented in the national legislature (not considering non-democratic countries such as China, Vietnam, and Iran). There are currently 5,362 members of state legislatures, only 10 of whom are members of a political party other than the big two: one Libertarian from Nevada, and nine members of the Vermont Progressive Party, all but one of whom were elected as both Progressives and Democrats (under a “fusion” ticket).

The state-mandated, direct party primary election (“direct” in the sense that voters chose candidates, not delegates to conventions who choose candidates) was not created by reformers intending to democratize a boss-run the system. As described by Alan Ware in The American Direct Primary, party officials welcomed state control over nominating procedures as a way to control those who might “bolt” from the party, to reduce the power of urban sections of the party, to gain partisan advantage, and to bring order to what had been a decentralized process of county and ward-based delegate election meetings (caucuses) and conventions that became less manageable as America became more populated and urbanized.

Over time, the direct primary had effects that were neither intended nor foreseen. Once the states ran party elections, they also had to determine by law who was eligible to be a party member, preventing parties from rejecting or removing unwanted members. This also meant that the parties had no control over who could use their name to stand for election. The parties became susceptible to intervention by outside forces — which has happened repeatedly in the 100 years since the direct primary system was established, notably:

- the transformation of the Democratic Party from a primarily conservative force to a quasi-labor party under FDR. When Roosevelt was seeking the Democratic Party nomination, the “conservative” party chair “considered him an out-and-out radical, and in order to block his nomination encouraged other Democrats . . . to enter the field.” Patrick J. Maney, The Roosevelt Presence: The Life and Legacy of FDR, p. 37.

- the takeover of the Republican Party by hard-line conservatives, first with the nomination of Goldwater in 1964 and later, following a concerted effort by the New Right, the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. The “Movement Conservatives” were so successful in their takeover of the Republican Party that they forced out all vestiges of New England and Midwest liberalism from the party — the element that was the true legacy of the original anti-slavery party of 1854.

- the rise of the Tea Party following President Obama’s inauguration in 2009, working within Republican Party primary elections to nominate candidates further to the right than “establishment” Republicans.

- the nomination of Donald Trump, previously a registered Democrat and at one time considering a run for president as a candidate of the Reform Party, as the 2016 candidate of the Republican Party.

Primaries were fatal to the development of independent political parties. As early as 1925, the Conference for Progressive Political Action, including representatives from labor unions and the Socialist, Progressive, and Farmer-Labor Parties, held a convention to “consider the formation of a permanent independent political party. The task was virtually insurmountable, however, as the heterogeneous organization had split over the fundamental question of realignment of the major parties via the primary process vs. establishment of a new competitive political body. The railway unions, whose efforts who had originally brought the CPPA into existence, were fairly solidly united against the third-party tactic, instead favoring continuation of the CPPA as a sort of pressure group for progressive change within the structure of the Democratic and Republican Parties.” (Source: Conference for Progressive Political Action: Organizational History)

Today, most Americans accept restrictions on new party access to the political process (if they even know about them) because there is are essentially no barriers to entering one of the two official parties. But primary elections open to anyone who self-identifies as a “Democrat” or “Republican” combined with severe ballot restrictions on new parties have produced a no-party system. Elections are focused around personalities, and party organizations (although still mandated by most state laws) are usually powerless vestiges. Mass-based organizations are focused around campaigns, and do not survive beyond a single election cycle.

In a way, primaries have become the first round in a two-round election system. This development has been formalized in the three states that require all candidates to participate in a single “primary” election. In Louisiana, no party labels are permitted on the ballot and the first election round, held on Election Day, is conclusive if any candidate wins a majority. In California and Washington, the first round is held on Primary Election Day (which in California is five months before Election Day) and the top two finishers, regardless of vote share or party affiliation, continue to a second round in November. The original version of the California “blanket primary” law was invalidated by the U.S. Supreme Court: Justice Scalia, writing for the majority, said the law violated the association rights of political parties by forcing them to have their nominees chosen by non-party members. He allowed, however, that the system would be constitutional if no party affiliations were listed on the ballot, as in Louisiana (California Democratic Party v. Jones). Washington, whose blanket primary system was also invalidated by the Jones ruling, changed its law so that the election was officially nonpartisan but candidates could identify their own party preference on the ballot. In a subsequent ruling, Justice Scalia said that this revised scheme was a ruse to circumvent party rights; however, this time he was in the minority, and the Court let the law stand, primarily because no election had yet been conducted under the new system (Washington State Grange v.Washington State Republican Party). Both states use this nominally non-partisan blanket primary today.

In important ways, though, primary elections are not like preliminary elections in two-round systems:

- In most states, primaries are only open to self-identified party members, or in some states open to party members and independents but not to members of other parties.

- In a few states (Connecticut and for statewide offices in Massachusetts), parties still have some control over who gets on the primary ballot.

- Other than the three states listed above, minor party candidates and independents are generally excluded (at least in practice, if not in principle) from primaries.

- There is no majority requirement in the primary itself, and it is not uncommon to have multi-candidate elections where the winner receives only 25%-35% of the vote. Several southern states require a runoff if no candidate in the primary wins a majority. This policy is a legacy of one-party Democratic rule when discriminatory laws and violence kept African-Americans from voting, eliminated party competition, and therefore made the primary election the only one that actually counted.

- Primary elections may be held many weeks or even months (as in California) before the general election, and in part because of the timing, turnout is typically very low.

Only one state, Georgia, requires that the top two finishers of a general election participate in a run-off election if no one receives a majority. Ironically, Georgia also has some of the most restrictive ballot access laws: “Georgia’s petition requirements for minor party and independent candidates for U.S. House — they must collect approximately 20,000 valid signatures, notarize each petition sheet, and pay a filing fee of over $5,000 — is so severe that no candidate has been able to surmount the requirement since 1964.” Richard Winger, Supreme Court continues record of hostility to minor parties and independent candidates. Therefore, the run-off requirement is rarely relevant or invoked.

Despite the pervasive discriminatory laws, many polls have found that Americans support the idea of new parties participating in politics.

How can the American political system be opened to new parties? I will explore the following elements in a future post:

- The fear of parties, including plurality winners and “extremists.”

- The conflicted Supreme Court rulings on the rights of major and minor parties and the potential for reform through lawsuits.

- How the “top two” blanket primary system could be a model for reform (or not).

- The potential for proportional representation systems such as ranked choice voting: could PR be the route to multipartyism, or is it the other way around?

- The role for Federal intervention in the national election system.

- The special case of electing the U.S. president.