A President Trump is a threat to U.S. democracy for two major reasons:

- despite the intentions of the Framers of the Constitution, the U.S. president has become extremely powerful due to the size and reach of the Executive Branch, the proliferation of White House officials and lawyers that can give legal cover to presidential actions, powers claimed by previous presidents to conduct policy and protect national security, particularly in a state of emergency, without the approval of Congress, and the proliferation of signing statements that purportedly allow the president to ignore laws passed by Congress;

- the next U.S. president will appoint at least one and probably several justices of the U.S. Supreme Court, which has become an unelected, higher branch of the legislature, due to its self-appointed power to overturn acts of Congress and its final word on the meaning of an old, brief, and ambiguous Constitution that is extremely difficult to amend through other means (other than by changing the Justices of the Supreme Court).

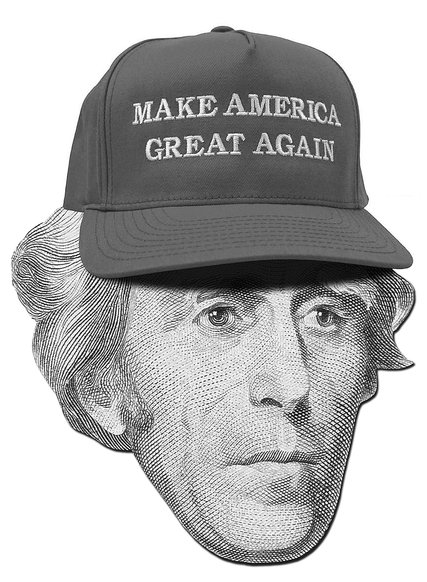

We Americans are being warned that a Trump Presidency would mean the end of our democratic republic. As I noted previously, Andrew Sullivan is calling a Trump victory “an extinction-level event” for “our liberal democracy.” Last week, a Washington Post editorial opined that Trump’s “contempt for constitutional norms might reveal the nation’s two-century-old experiment in checks and balances to be more fragile than we knew,” and added, “Most alarming is Mr. Trump’s contempt for the Constitution and the unwritten democratic norms upon which our system depends.”

How did it come to pass that a single election could mean the end of U.S. democracy? Do we really depend on unwritten constraints on power to prevent a descent into tyranny? The Framers of the Constitution thought they were creating a national government with limited powers. They believed that Congress would be the strongest branch, and, although they were keenly aware of the need for an executive (which the first U.S. constitution lacked), they believed that “the executive was to have a decidedly supporting role, more analogous to an errand boy for Congress than a powerful leader who sets the nation’s course of action” (Carol Berkin, A Brilliant Solution, p. 82). While the Framers carefully itemized the powers of Congress, they provided only the barest description of the president’s job. The president was to grant pardons, appoint justices and government officials (with advice and consent of the Senate), negotiate treaties (to be approved by a 2/3 majority of the Senate), act as Commander in Chief of military forces (when war is declared by Congress), and “take care that the laws be faithfully executed.” Importantly, in their zeal to reduce the power of Congress, the Framers gave the president the power to veto legislation, greatly increasing the power of the presidency. In the words of two political scientists:

the Constitution’s incomplete contract sets up a governing structure that virtually invites presidential imperialism. Presidents, especially in modern times, are motivated to seek power. And because the Constitution does not say precisely what the proper boundaries of their power are, and because their hold on the executive functions of government gives them pivotal advantages in the political struggle, they have strong incentives to push for expanded authority: by moving into gray areas of the law, asserting their rights, and exercising them, whether or not other actors, particularly in Congress, happen to agree. (Terry M. Moe and William G. Howell, The Presidential Power of Unilateral Action)

Another reason the power of the presidency has increased over time is the president’s ability to claim a popular mandate. The electoral college method of electing the president was a curious compromise that never worked as the Framers intended. As new states were formed with less restrictive voting qualifications, and old states loosened theirs, America became the only mass democracy in the world (at least for male, European-Americans) by the 1830s. After denouncing the “corrupt” (but Constitutionally proper) election by the House of Representatives of John Quincy Adams, with 31% of the popular vote compared to his 41%, Andrew Jackson won the next two presidential elections. “The Jacksonians’ chief institutional innovation . . . was to vaunt the power of the executive, selected, as never before, by the ballots of ordinary voters, and not (with the glaring exception of South Carolina) by the state legislatures–as the only branch of the national government chosen by the people at large” (Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln, p. 514). Jackson’s claim to a mandate was only that he was co-equal with Congress. It was not until Woodrow Wilson in the 20th Century that a president claimed to be more powerful than Congress (see Robert Dahl, Myth of the Presidential Mandate).

More recently, we have been warned about the danger of a charismatic outsider such as Trump winning the presidency. In The Decline and Fall of the American Republic (2010), Bruce Ackerman writes:

I have been trying to shake Americans out of their complacent assumption that the past is prologue and that we will continue to keep the presidency under constitutional control. The presidency of the twenty-first century is a vastly different institution from its predecessors. Instead of supposing that the Founders told us (almost) all we need to know, we should recognize that the modern system generates three distinctive dangers.

The first is extremism, which I have been defining in terms of a president’s distance from the median voter . . . [A President] should not be allowed to lead the nation on a great leap forward through executive decree. Especially since his self-righteous campaign might actually be pushing the nation over the precipice into moral disaster. After all, his appeal to left or right extremists hardly ensures ethical insight. All it guarantees is a great deal of applause from supporters as the president breaks through institutional roadblocks to lead the American People to the promised land. The modern primary system makes this extremist scenario an all too real possibility.

It also promotes a second great danger: a politics of unreason. Once presidents have relied on their media gurus to sound-bite their way to the White House, they are naturally predisposed to believe in their near-magical powers.

Ackerman’s third great danger is the unilateral powers possessed by the modern president, which he details at length, stressing that most of them are recent innovations in the history of the Republic, dating back to only the past 40 years or at most to the New Deal period.

Ackerman blames much of the problem on the post-1972 presidential primary system, which gives voters rather than party insiders the major voice in determining the party nominees. However, it is wrong in my opinion to see the problem as too much democratization, but rather, at its root, the duopoly of the two official parties that stifles fair and open competition and reduces participation. The duopoly typically works against outsiders but, as best seen in the Trump case, can be used by an insurgent who lacks establishment support and lacks majority support as well, but can still win in elections when nearly half the voters stay home, in part because they do not feel they have a first-choice candidate to support. Moreover, since the separate state elections that determine electoral votes are all plurality elections, a candidate can win with less than a majority, as has happened 12 times. Ackerman supports the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact as the only achievable means to create a direct popular vote for president, thereby mitigating the risk of a plurality winner. (He also believes that Congress must pass supportive legislative for the NPVIC to be effective, in particular, to determine the official count of the national popular vote.)

Ackerman further summarizes some of the reasons to worry about what a charismatic, insurgent candidate could do upon winning the White House:

[Unlike President Obama,] the next insurgent president may not possess the same sense of constitutional restraint. He may insist on fulfilling his self-proclaimed popular mandate even if it provokes a profound constitutional crisis. And so long as he has enough partisan supporters in the Senate, the prospect of impeachment will not serve as a significant deterrent [since a conviction on an impeachment charge requires a 2/3 majority].

Ackerman emphasizes that these risks are relatively new in American history:

During the nineteenth century, the president worked without a significant staff. He governed through a cabinet containing independent political potentates who sometimes were outright rivals. . . . The young Woodrow Wilson was right to proclaim that America was then living in an era of Congressional Government (1885). . . . No longer. The Constitution is now governing a system in which an institutionalized presidency rules through a politicized White House that dominates the cabinet secretaries and sets the agenda for Congress. At the same time, the president plays a complicated game with his military commanders in an effort to gain their continuing support.

He adds that we should not be complacent based on past experience:

[S]uccess in bouncing back from the Civil War or Jim Crow or McCarthyism doesn’t mean that we are prepared to deal with the multiple challenges posed by the modern presidency. The past forty years suggests a darker view: Watergate, Iran-Contra, and the War on Terror each dramatized the perils of presidentialism to the general public. Yet these repeated explosions of blatant illegality have provoked increasing passivity. Only the Watergate crisis generated a sustained effort at structural reform, with Congress passing a series of landmark statutes to curb presidential abuse. These . . . proved inadequate, but there were two ways of responding to these initial failures: do better or do nothing. The silence has been deafening.

In a later post I will examine why the Supreme Court has been so important to American politics, what a Trump presidency would mean for the Court, and how in the long run, particularly with a Democratic victory, its role could be changed. According to the late political scientist Robert Dahl, the more the Supreme Court moves outside the realm of fundamental democratic rights, “the more dubious its authority becomes. For then it becomes an unelected legislative body. In the guise of interpreting the Constitution–or even more questionable, divining the obscure and often unknowable intentions of the Framers–the high court enacts important laws and policies that are the proper province of elected officials” (How Democratic is the American Constitution?, pp. 153-154).

The NY Times is reporting that “The commander in chief can also order the first use of nuclear weapons even if the United States is not under nuclear attack. . . . The president’s authority over nuclear decision-making challenges the Constitution’s clear declaration that only Congress holds the power to declare war. ”

So much for adherence to Constitutional principles. This might be a good time to rethink the power of a president to individually order a first use of nuclear weapons.

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/05/science/donald-trump-nuclear-codes.html